During the course of my mother-in-law’s slow, quiet slide into the abyss of dementia, I’ve become the ersatz matriarch of the family.

During the course of my mother-in-law’s slow, quiet slide into the abyss of dementia, I’ve become the ersatz matriarch of the family.

Mostly, it’s fine, pulling together a few Shabbos dinners a month and making sure everyone remembers each other’s birthdays. But for some reason, I’m not feeling it this Thanksgiving. I haven’t even been to the grocery store yet—just the thought of climbing around the aisles grabbing for the one unbruised potato is causing my intestines to entwine.

Surely losing my job has contributed to the ambivalence over two days worth of cooking that gets snarfed in 20 minutes, but the thing that’s been bothering me the most is that a threshold has been crossed: My mother-in-law no longer remembers me. She hasn’t said my name since the beginning of the summer, but her eyes would still spark when she heard my voice. The family singsong phrase “I love you love you love you…” could always evoke a response, though she hasn’t spoken any real words in months. Even if it took a few seconds, I could watch her face go from suspicion to scrunched confusion as her poor mind tried to latch onto something that matched. I could tell the second the synapse clicked: She would smile, the mystery of this person in front of her singing and waving solved.

Last week, though, the click never came. Her wonderful caregiver, Iris (whose nephew happens to be Auburn quarterback Cam Newton, a lil’ tidbit for all you SEC football fans) got her all fapitzed (that’s Yiddish for gussied up) in red for the JEA senior Thanksgiving lunch, complete with a spritz of the Chanel perfume that’s been collecting dust on the vanity for the last few years.

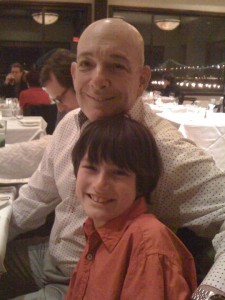

El Yenta Man’s eyes teared up when he smelled his mama. “She smells like Mom again,” he choked, placing his cheek against her neck for one more breath.

I knelt in front of her wheelchair (her ability to walk diminished right around the same time as her speech) for our usual ritual, but when I looked into her eyes and cooed our “love you” song, she looked back and shrugged. I tried a few more times, but the curtain of confusion never parted even a sliver, and that’s the first time in the five years she’s been diagnosed that I couldn’t get through.

Though one never knows with dementia, it appears that our family is nearing the end of having this dear lady around. I know what I need to do is step up and make this the best Thanksgiving ever—assign kitchen tasks to keep my father-in-law busy and out of the clutches of despair, make pies from scratch, encourage the children to learn a few new songs on the piano and have Iris put my mother-in-law in something fine, with a little spritz of Chanel behind her ears. Except all I want to do is scream at everyone to go out for Chinese and then zone in front of the TV, even if I have watch football all day. I’m making a lousy matriarch, more like Joan Crawford than Martha Stewart.

If my mother-in-law had her druthers, she’d let me spill my sadness and nod without saying anything for a while. She was the kind of matriarch who let everyone be who they were and do their thing while she quietly and without complaint shouldered the brunt of the shopping, the cooking, the napkin-folding, the wine uncorking, so it hardly looked like any work at all. Of course, as a good Southern Jewish girl, she somehow missed the entire women’s liberation movement of her generation, though when we discussed the feminism, she waved her hand and said she had always done everything she wanted to do.

If she could, she would tell me it’s very understandable that I should be feeling down about things and not so motivated to make a big fuss over a meal. She’d give me some simple shortcuts to make things easier, like buying instant stuffing (which is gross, but listen, though she is a fantastic and talented lady, between you and me, she was never much of a gourmet cook.) She’d also remind me how important I am to my family, and if I need help, I should ask for it. And finally, without guilt-tripping me or making me feel like an a**hole, she’d list off twenty or so amazing things in my life for which I can be grateful.

And what do you know? My father-in-law just called to volunteer to make the turkey. El Yenta Man said he’d make the stuffing. I’m still saddled with the shopping, the green beans and the pies, but if I treat myself to a carmel macchiato before I brave the florescent-lit purgatory of Publix, I can manage.

This may not be a Thanksgiving to remember, and maybe that’s the way it’s supposed to be. And I may end up being the kind of matriarch who makes reservations at Wang’s Chinese next year.